A winner of the Opencare’s 2015 Patients' Choice Awards for Dentistry in Brooklyn

Verified by Opencare.com

Professional Qualifications

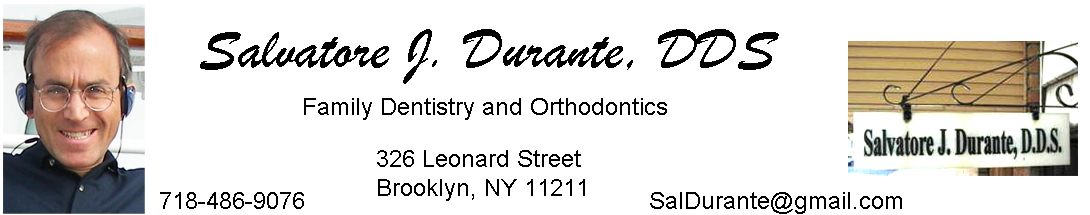

- D.D.S., New York University, 1981. Graduate training at New York Hospital. In private practice in Greenpoint / Williamsburg since 1982.

- Continuous continuing education

- Editor of GP: Journal of the New York State Academy of General Dentistry, 1990-1995.

How do I decide what new equipment to buy and what new procedures to offer?

Why am I a dentist?

Excerpts from an interview in The Ayn Rand Institute Newsletter, June 1991.

Question: How and when did you become interested in dentistry?

Answer: I actually decided to become a dentist when I was ten years old. After having been to several uninspiring dentists, I happened to go to one who projected such confidence and ability that he became a role model for me. Part of what inspired me was the way he spoke about how being industrious could lead to independence. More concretely, he showed me that what he was doing didn't have to hurt.

Q: Most people don't enjoy going to the dentist or consider dentistry a very exciting profession. Do you ever have difficulty maintaining a positive feeling about the work you do? Or does this seems like a silly question to you?

A: No, it makes sense. Part of the challenge of dentistry is making people comfortable within a naturally uncomfortable situation. Satisfaction comes not only from curing disease, but in calming someone's fears, in showing a patient that this isn't so bad after all - which is exactly what my dentist did for me when I was ten years old. Plus, on a more concrete level: each procedure in dentistry is actually rather creative, like a little work of art; with each procedure there's a sense of accomplishment, of getting something worthwhile done. I might experience that ten times a day. It's marvelous.

Q: When did Objectivism [the philosophy of Ayn Rand] enter the picture?

A: During my college years at New York University. While I had a strong scientific background, I had also absorbed some liberal New York attitudes. At NYU, I met someone from another part of the country who forced me to question my left-wing ideas by constantly asking, "Well, why do you say that?" Eventually this person tired of just discussing one idea after another with me and gave me Atlas Shrugged. I enjoyed the novel, but didn't see it as anything more than a good novel at that point. Later, when I read it a second time, I was surprised to see - from the marginal notes I had made the first time through - that while my initial reactions to Ayn Rand's characters and ideas were quite skeptical, by the end of the novel she had convinced me.

Q: So even though you were convinced after the first reading, you didn't consider yourself an Objectivist at that point?

A: No. I knew that I could no longer call myself a liberal, but I still had too many questions. I had always been a valuer - it's just that I thought liberal values were the ones I should pursue. When I questioned what those values were based on and what they would lead me to, I realized I didn't have the answers. Then, in dental school, I had another strong role model - an instructor who held his head high and had great character and self-confidence. He seemed more well-rounded and knowledgeable than the other instructors, about areas of life other than dentistry. I once asked his advice on what seemed to me a very innocent question: Should I carry disability insurance? By way of response, he sat me down and asked me if I had read The Fountainhead, mentioning the scene in which Keating asks Roark if he should accept the Paris art school scholarship; then he asked how I could stand to let anyone make decisions for me. I was intrigued, and proceeded to read The Fountainhead. He then gave me The Ominous Parallels, which really fascinated me. That year, I attended Dr. Peikoff's course, "Understanding Objectivism." I went on to read first the non-fiction, then the rest of the fiction, and to take all the taped lecture courses - and I met my wife at a taped lecture course.

Q: Does Objectivism help you in your work?

A: Yes, primarily in evaluating and dealing with others. There are philosophies that hold honesty and integrity as virtues, but only Objectivism actually validates them. I often hear from patients, "Can we write such-and-such on the insurance form? I hear other dentists do it." The idea of a short-range fix, a short-term gain - I see immediately what's wrong with that, even in a corrupt system. Luckily, dentistry is not nearly as bad as medicine, not yet.

Q: Thanks in part to your efforts, I gather. Tell me about your professional activism.

A: In 1985, I heard Dr. Peikoff's talk on "Medicine: The Death of a Profession." That stimulated me to think about the status of the dental profession. I did some research and found out that the American Dental Association (ADA) had a standing policy to lobby for inclusion of dental benefits under Medicare, and I decided that I was going to get that policy reversed. It took a couple of years, working within the system, but I and several other dentists finally accomplished it.

Q: What exactly did you do?

A: The first thing I did was send copies of "Medicine: The Death of a Profession" to a few key people, with a cover letter saying basically, "This is true, and you should do something about it by changing the ADA's policies." Someone in the ADA advised me that having a philosopher from the outside tell the ADA what it should and shouldn't do wouldn't go over very well. He suggested that I become the spokesman for the policy change, and that's what I did. At a nationally attended ADA meeting, I delivered a lecture entitled "Medicare: What It Did for Medicine, It Can Do for Dentistry." I detailed the development of Medicare and the ADA's policy to seek to expand Medicare to include dentistry, and I showed how that policy was not in the interest of dentists. An editor in the audience asked me to turn the lecture into an article for a national dental journal, which I did. Then I started sending it to ADA representatives at the state level. Some of them contacted me and helped me bring the issue up to the national level and put it to a vote. Prior to the vote, we sent information to all 450 members of the ADA's House of Delegates. The policy was overwhelmingly rescinded.

How do I decide what new equipment to buy and what new procedures to offer?

When I graduated New York University in 1981, I was very excited about what "modern dentistry" could deliver. In those days, new adhesives had just made possible tooth-colored restorations. With these new "super glues" it was often possible to repair a tooth by bonding a white filling to the tooth instead of having to repair it with a crown. While crowns are still often the only way to save a tooth, these white, bonded fillings have delivered everything they promised and more - including repairing severely broken-down back teeth, closing spaces between front teeth, and improving the shape and color of front teeth. Since then, further advances in adhesive technology have made possible porcelain laminates which provide a longer lasting and even better esthetic result. And the advances are still coming at a dizzying rate.

And that's only in one area of dentistry! Similar advances are being made in other areas as well - like alternative ways of doing root canal therapy, new crown-and-bridge materials and techniques, implants, sterilization and disinfection, computerized x-rays, air-abrasion, lasers, intra-oral cameras . . .

An innovation must satisfy the following criteria before I will add it to my practice. It must be a substantially better way to do something for my patients without disproportionately raising costs, or it must lower the cost of doing something without lowering quality. For example, presently I believe that intra-oral cameras and lasers are very expensive toys that would bring very limited benefits to my patients while raising costs substantially; and I have decided that air-abrasion and computerized x-rays are major improvements in dental care that also actually help control costs.